By Mariah Montgomery, National Campaigns Director

Whether we work in an office, at a warehouse, from home, or on the road, we all want good jobs that let us look after our families and contribute to our communities. But app-based rideshare corporations like Uber are exploiting their workers through a business model that pushes drivers into unsafe situations, creating a safety crisis for drivers all across the country.

Groups of drivers have been coming together to push back on this exploitive business model for years. And as Uber has slashed pay and pushed more drivers into danger, in the past months there’s been a surge in organizing. This spring, we partnered with driver groups from across the country — California Gig Workers Union, Chicago Gig Alliance, Colorado Independent Drivers United, Drivers Union WA, Gig Workers Rising, New York Taxi Workers Alliance, and Rideshare Drivers United — to take coordinated action in six cities, and (for the first time ever) bring the fight directly to Uber’s shareholder meeting.

Drivers are organizing for living wages, safety, and to end unjust terminations. They’re building power that is becoming more and more difficult for app corporations to ignore. Here’s the story of how they're doing it:

Drivers are facing a safety crisis

In 2016, Marianna Porras, a leader with Gig Workers Rising and single mother in Oakland, CA, suddenly became the sole provider for her children. She needed a job that would pay the bills and give her the flexibility to care for her family. In Uber, Marianna found just what she needed: a job with decent pay and a flexible schedule. However, things have deteriorated over the past few years. Uber has been cutting driver bonuses and taking larger and larger percentages of ride fares, forcing drivers like Marianna to work more while being paid less.

Marianna now drives at least 8 to 10 hours each day to make ends meet. While Marianna used to be able to work full time and pay her bills, Uber is now pocketing such huge portions of each fare that “the payouts are nothing; there would be literally like $4 per ride, and the passenger is paying like $20.” And this pay doesn’t include gas, insurance, car maintenance, cleanings, or other things Marianna needs to do her job. “They lie about how much money you make,” Marianna shares, “They’re exploiting people.”

“They lie about how much money you make. They’re exploiting people," shares Marianna Porras with Gig Workers Rising.

Low pay and the constant threat of deactivation have also made working conditions unsafe for drivers like Marianna. If a customer complains because a driver cancels a ride – even if the driver feels unsafe – Uber can deactivate the driver’s account without any investigation or justification. The threat of deactivation coupled with low pay can push drivers into taking unacceptable risks on the job, creating a safety crisis for drivers.

Marianna says she’s had so many scary experiences while driving, from passengers pressuring her for her phone number to one passenger even placing an Airtag in her car to track her. Marianna says sometimes passengers “won’t get out of the car until they call my phone and see if it rings to see if I’m giving them my right number,” and she doesn’t know what to do. She reported these incidents to Uber a number of times, but says “they never did anything about it. Nothing.” Now, Marianna doesn’t drive at night anymore because she feels so unsafe: “I have kids I have to get home to.”

App corporations like Uber have created some of the most dangerous jobs in the U.S. Recently, the Strategic Organizing Center conducted the largest comprehensive safety survey of app-based rideshare drivers to date. They found that two-thirds of all drivers who responded said they had been threatened, harassed, or assaulted at work in the last year. And 59% of drivers said they accept rides even when they feel unsafe out of fear that they’ll receive negative reviews and be deactivated by Uber.

Drivers of color (the majority of the workforce) face the brunt of this safety crisis. 72% of drivers of color who were surveyed reported experiencing some type of threatening or violent behavior, compared to 63% of white drivers. And 70% of the drivers of color surveyed said they accept rides when they feel unsafe for fear of deactivation due to negative reviews.

When talking about her experience, Marianna couldn’t help but think of the other drivers out there that face similar dangers: “I feel bad for the people who went out there and did their rides and did their food deliveries and didn’t make it home.”

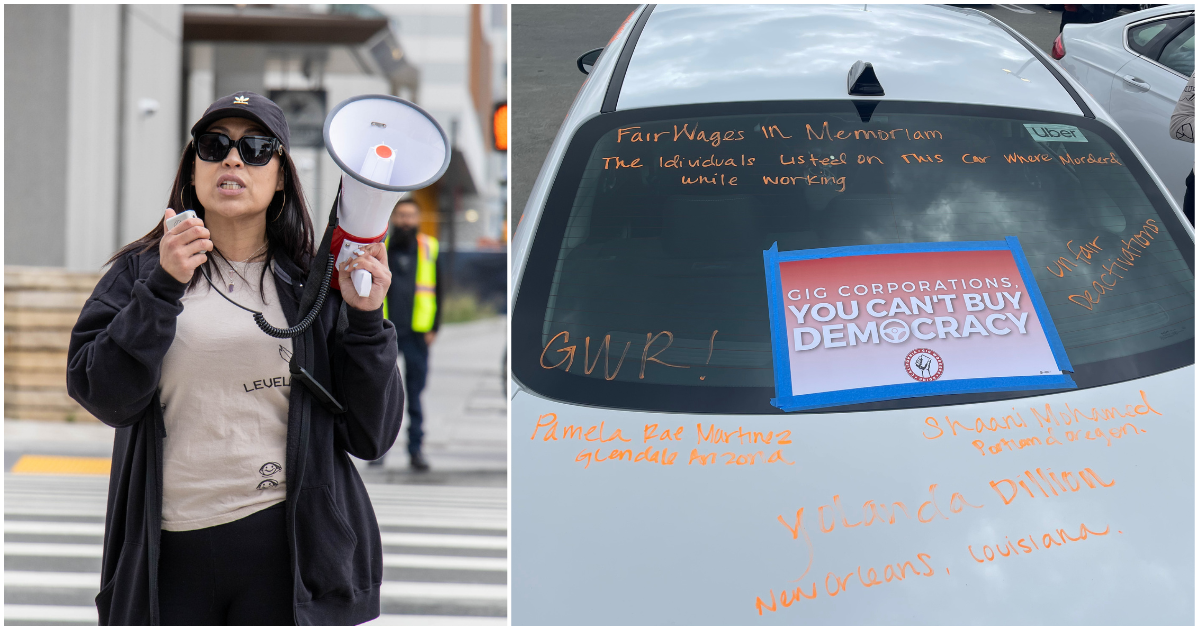

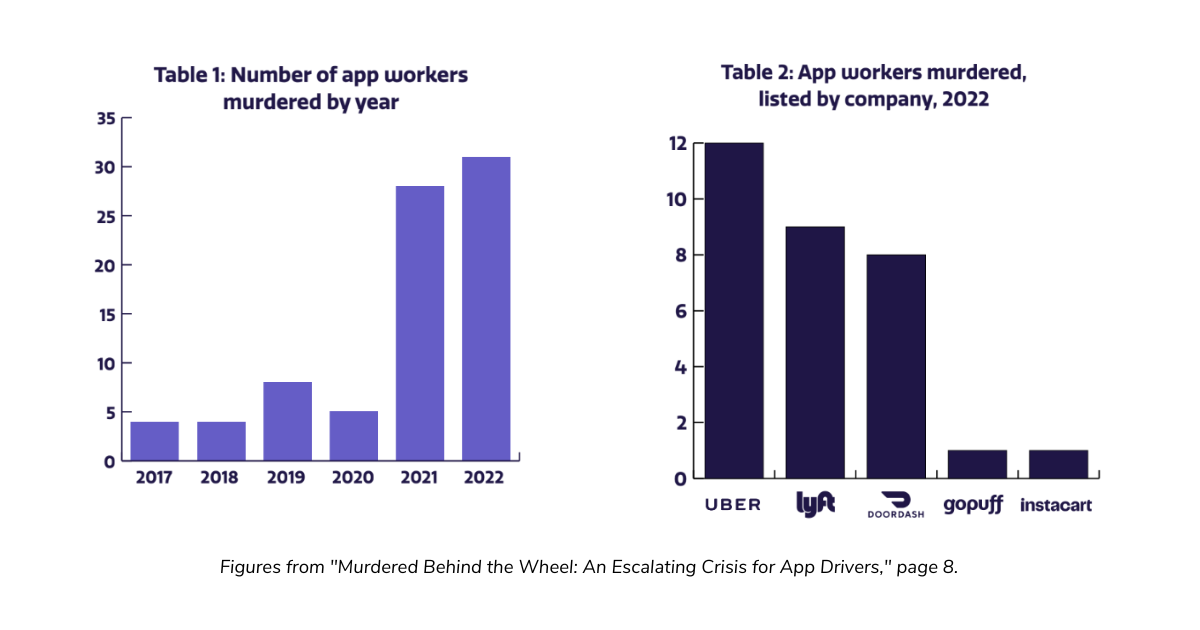

According to a recent report we co-published with Gig Workers Rising and the Action Center on Race and the Economy, too many drivers don’t make it home. In 2022 alone, at least 31 app workers – primarily people of color – were murdered on the job, bringing the total up to more than 80 drivers murdered in the past five years.

This is why Marianna has been organizing with other drivers in Gig Workers Rising, a community of app workers fighting for better wages, working conditions and jobs. She hopes that, by organizing, drivers can win safer working conditions.

Breaking down barriers to organizing

Michael Machar – a leader with Colorado Independent Drivers United – has been driving for Uber for the past 5 years. As an organizer and community leader, he sees the significant challenges drivers face as they organize across the country, reflecting that “with this type of work… there's no particular place you can catch up to mobilize people because everybody is in their cars.”

The app-based business model isolates drivers. Drivers work from their cars, with no shared office or easy way to communicate with other drivers. So to organize, drivers have had to get creative.

Organizers like Michael go to where they know other drivers are: airports, parking lots, and online. Michael spends a lot of his time at the airport connecting with drivers. “This is the only place that you can catch up with people,” he says, “You come here, wait, and then everybody will go to the bathroom, and then that's when you can talk to them.”

Drivers have also been sharing resources and creating spaces online where drivers share their stories and warn each other about safety issues, such as through Facebook and Whatsapp groups. It was one of these spaces in which Marianna warned drivers that a passenger tried tracking her with an Airtag, sharing screenshots to raise the alarm. Drivers are using these digital meeting spaces to connect with each other across geographies and time zones, coming together around their shared experiences and showing each other they’re not alone.

And driver organizers tap into offline communities. Many drivers are immigrants, who hear about the job from neighbors, relatives, or friends from a church or mosque. Drivers are using these same networks to organize, often in Spanish, Somali, Arabic, or any of dozen other languages.

And it’s been working. Michael says the movement has been growing quickly. He hopes that “by this summer we can grow and be able to tell other drivers who are maybe hesitant to organize, please trust yourself. If you trust yourself, there's no reason not to trust other drivers because you're facing the same thing.” Because of organizers like Michael who meet drivers where they’re at and maintain active social networks online, drivers have been breaking down barriers to organizing, connecting with and building trust in each other, and taking action.

"[For] drivers who are maybe hesitant to organize, please trust yourself. If you trust yourself, there's no reason not to trust other drivers because you're facing the same thing," says Michael Machar with Colorado Independent Drivers United.

But coordination hasn’t been the only challenge these workers face. Uber has been taking action of its own to stop change. This spring, Uber beat back a bill drivers brought forward which would have allowed Colorado rideshare drivers to know how much of each fare they receive from each trip, and how big of a cut the companies they work for take out of each fare. In Minnesota, Uber threatened to leave the state if drivers were successful in winning a minimum wage law there. Workers in Denver got a message from Uber after recent organizing activity, suggesting they had broken unnamed airport policies—which drivers interpreted as retaliation for fighting back.

“A lot of us are already traumatized,” Michael says, “and we just keep getting pounded from Uber and Lyft. They're using intimidation language against drivers.” But these barriers have only fueled the fire of drivers’ righteous indignation at Uber’s exploitation. Drivers have been doubling down on their organizing efforts, recognizing they have great power together.

“They’re stealing from me. That's stealing from you,” is Michael’s philosophy. “Why not trust in yourself and me? And let's fight together.”

Taking the fight to the streets — and to Uber’s shareholder meeting

Despite the multiple barriers to organizing, drivers have used their ingenuity to build relationships and fight together across languages, experiences, and geographies. This year they also made history by taking the fight all the way to Uber’s annual shareholder meeting for the first time.

On May 4th, just days before Uber’s annual shareholder meeting, we worked with driver groups to coordinate a national day of action with over 1,000 drivers taking action in cities across the country to demand these companies prioritize worker safety.

Then at the meeting, Jocilyn Floyd – an Uber driver and leader with Chicago Gig Alliance – presented a resolution on behalf of drivers calling on Uber to be more fair and transparent in how they pay drivers and to end unfair termination practices that pressure them into unsafe situations. The resolution was drafted in consultation with drivers around the country and submitted by PowerSwitch Action.

Jocilyn started driving with Uber in 2015 so that she could care for her son with special needs. After an attempted carjacking by a passenger, she’s felt unsafe as a driver ever since. “I have my head on a swivel. I don’t leave my doors open, I don’t leave my windows open. There is no way you can live a normal life driving Uber.” And like many other drivers, Jocilyn is done with being forced to choose between putting food on the table and staying safe at work.

This is why Jocilyn shared her story on behalf of drivers all across the country. As Uber was celebrating record revenue, Jocilyn urged shareholders to vote for Uber to pay drivers fairly and end unfair deactivation practices as two key ways to make driving safer. “As a mom, when I am deciding if I should cancel a ride or ask a passenger to get out of my car, I’m weighing the possibility of not seeing my family again,” Jocilyn told shareholders.

Uber tried to downplay the health and safety crisis to block the resolution. Jocilyn shares that “I was disappointed in their responses. They showed their true colors. They don't care about us or our families, about our rising concerns over safety.” But she’s not letting that stop her from organizing and speaking up. “I’m glad I had the opportunity to share those words with the board of directors and shareholders,” she reflects, “and for them to hear from someone who is doing it.” And she doesn’t plan to stop there. Drivers like Jocilyn are continuing to organize, speak up, and fight back.

“If Uber drivers stopped working, if rideshare driving ended as we know it, there would be a crisis. We’re just as essential as anyone else," shares Jocilyn Floyd with Chicago Gig Alliance.

And the fight is gaining momentum. Drivers are making history by breaking down all of the barriers thrown at them, making connections and forging relationships in creative ways, working together despite Uber’s attempts to shut them down, and becoming a force that Uber will not be able to ignore. As Jocilyn put it, “If Uber drivers stopped working, if rideshare driving ended as we know it, there would be a crisis. We’re just as essential as anyone else. The only real way to be safe is to continue to organize.”