By Felicia Griffin, Deputy Director, and Christina Rosales, Housing and Land Justice Director

Felicia: Christina, we are so excited that you’ve joined us here at PowerSwitch Action as our new Housing and Land Justice Director. You recently launched Dot’s Home, a video game about the housing crisis.

Can you tell us more about the project, and how you got involved?

Christina: I previously worked for Texas Housers, which is a statewide housing advocacy group. Just like PowerSwitch Action, Texas Housers was a part of the former Just Cities and Regions portfolio of the Ford Foundation. Back in early 2018, Ford started a narrative cohort, Rise-Home Stories Project, which led to the creation of this game.

The big thesis of this cohort was that if we changed the way we talk about land and home in this country, if we uplift our community shared values and narratives to downplay the dominant narratives of scarcity and individualism, that we could move policy, and we could build and strengthen our base for the purposes of the housing justice movement.

We got trained in narrative design and narrative organizing, and then we committed to projects that applied all of this knowledge to put forth inspiring, values-driven narratives. There were a number of projects — PowerSwitch Action was involved with a children’s book, Alejandria Fights Back!, and there’s also a podcast, an online puzzle platform, and a web series.

But the project that I helped co-create is a video game. And I’m really very lucky that back at Texas Housers, when I came back from this convening and said, well, I’m going to make a video game, the leadership said, “That’s great. We trust you. We don’t know what you’re talking about, but we believe in your vision and you’re really passionate about it. So go forth and do this.”

The reason we chose a video game as the medium, and chose to tell the story about housing issues in communities of color in America, is because so often we see this sense of inevitability about housing and land in this country.

We’re told that the market decides everything. And people of color, people like me, who’ve grown up in a lot of turmoil related to land and home, are told that’s just the way it is.

We’re told, “You’re going to have to deal with it, work your way up, work really hard, and you can buy a house and build your wealth.”

And we know that’s not true. The choice set in front of us was created by policies that were intentionally made to exclude people of color. There is nothing like a video game to make you believe that you have agency and choice. We knew this was the only way to get at that theme of choice and self determination. So that’s why Dot’s Home was a video game.

Felicia: Can you tell us a bit about what happens in Dot’s Home?

Christina: Yeah, no spoilers — but I can tell you how the game works.

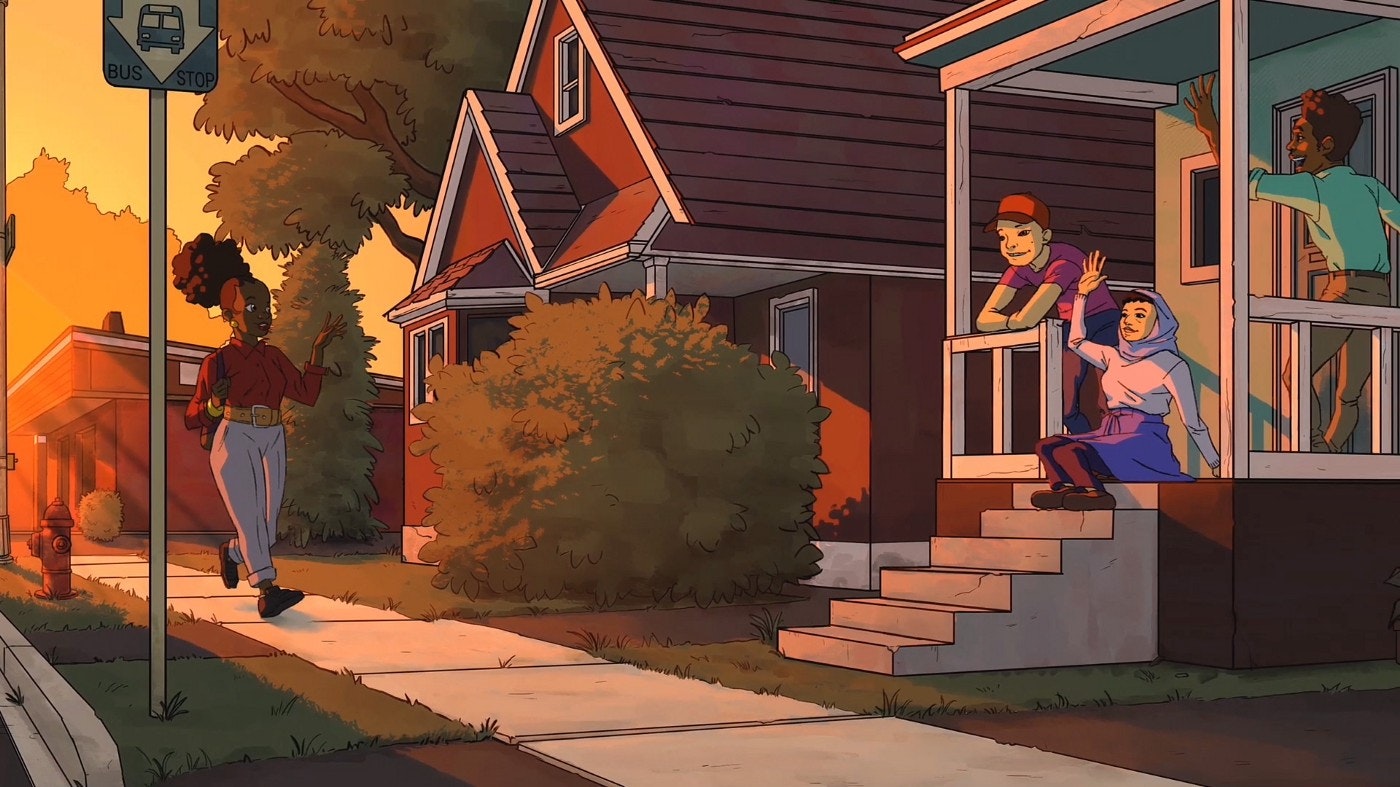

It’s a narrative-driven video game and it’s a pretty simple concept. It’s like a point-and-click adventure game. The player follows Dot, who is a young black woman in her twenties, living in Detroit, and she’s living in her grandmother’s beloved home.

It’s set in the present day. Currently in a lot of neighborhoods of color there are predatory speculators who are trying to buy up homes and land and turn them for a profit. So the same thing is happening in Dot’s grandmother’s neighborhood. That’s the first big theme that the player confronts.

It’s important for Dot to understand how her family came to the present day. So throughout the game, the player goes back in her family’s history and confronts key decisions that they had to make to get to where they are. Every decision — navigating home-buying in Redlined Detroit in the 1950s, urban renewal in the 1990s, post-foreclosure crisis in early 2010 — in all of these periods, we see how the same themes come up over and over. Every time, the player advises Dot’s family to make a choice, and it changes Dot’s present day.

Ultimately the player is directed based on their choices to one of three endings. So it’s a little bit sci-fi, it’s a little bit comic book universe. It’s important for people to know that it’s a story about family, and it’s a tender, funny story, but there’s also time travel, and housing policy.

Felicia: Who do we hope, or who do you hope will play this game?

Christina: One thing about games that I think is interesting is there are definitely people who love games and believe in them, and see them as a work of art. So there are two things I hope can happen. One is we get a lot of people who play games exposed to these issues, so that they become part of our base, and they sing from our hymn book about housing justice and racial justice. So there’s that.

But really, the people we had in mind — the target audience — is black and brown young people, millennials and a little younger, high school age. Because we know that they’ve been sold this lie that if you work hard you can get everything you want, and you can just rise through the ranks, you can build wealth, and you just work for yours, and worry about yourself. And we know that our generation and younger are skeptical of that, and they’re questioning that. So we want to validate their experiences.

Some of them are super comfortable with games. Some of them are not. This game is very easy for anyone to pick up and play. It’s going to be on mobile. You can play it on your phone. It takes about an hour.

And then the other thing is — this is just a side note — but there is a lot of doubt about video games as an art form, as a valid piece of storytelling. I was one of those people who didn’t play games before this experience. And as I did my research about games, I found that with some of the games I played, it was like curling up with a book. It’s a beautiful way to experience a story. So in addition to reaching gamers, reaching our target audience, I also think this is a powerful way to help people to see that video games are a valid form of art and storytelling.

Felicia: The visuals are beautiful. Can you talk a little bit about the creative process and how you think about the role of art in the work that we do and in policy work?

Christina: Yeah, the lead artist for Dot’s Home is a comic book artist named Sanford Greene. He designed the characters and a lot of the backgrounds along with our first lead developer Neil Jones. A studio called Weathered Sweater also helped with a lot of the art and design and animation.

But the process was really interesting, because a key tenet of the Rise-Home Stories project was that organizers and advocates were not just clients of artists, we were co-creators. So a lot of the concepts and stuff, they were dreamed up by organizers. For instance, I’m very into making clothes, I sew. And so you see a lot of that in Dot’s grandmother’s home. And we decided on the outfits, we decided on what Dot would look like. So everything was done in very close collaboration, with the Rise-Home Stories team and these really fantastic artists. To be frank, I was a little star struck to be working with people like Sanford Greene and writers Gita Jackson and Evan Narcisse.

I think art is such an important part of our work because it allows us to envision something that maybe doesn’t exist, or maybe it exists in pockets of our society. But when we use art to inspire a vision, it’s so joyful and motivating to think about what could be, and we can picture it in our heads. And then when we work with artists, they just have another way of expressing this vision, that I can’t access as a policy wonk and organizer. But these folks can.

I think it’s just important to continue working on integrating art and media and this kind of joy in our work, because our work is so draining and tiring sometimes. It’s full of this score sheet of wins and losses in policy. And I think that’s draining. If we work with art, it allows us to imagine something different and work towards something that maybe isn’t measurable, but it’s still about improving the quality of our life.

Felicia: Awesome. You are so amazing! So I’m going to give you a three-part question: when, and how can folks get access to this game, and what’s next?

Christina: Folks can download the game from Steam and itch.io, and it’s free to play.

And then a few weeks from now it’ll be available on Android and iPhone. We are doing a live play-through on the October 22nd launch day at a festival called Indiecade. I will be live-playing, and live-streaming me playing Dot’s Home for the world, alongside Evan Narcisse who is one of the lead writers of the game.

And what’s next? It’s just really getting this game out there. I think it can be a very powerful community engagement tool. There are a lot of really complicated concepts that are told through family in this game.

I think Dot’s Home could really help de-wonkify talks about zoning, and community land trusts, and fair housing. The game talks in an accessible way about community shared ownership of land and housing as an important solution, not only for building permanently affordable housing, but really thinking about communities’ self-determination and agency in land ownership, and in creating a multiracial feminist democracy.

So I’m hopeful that our network and our partners can use it for community engagement. And also that we can bring it to classrooms and youth organizing, because there is something very youthful about games and about this story in particular, and the art.

One other thing I’ll say is: With this game, we’re not asking players to walk a mile in Dot’s shoes or in her grandmother’s shoes. We’re asking our audience to accompany this family through this journey. Unless you’ve experienced this, nobody’s going to really understand how characters like Dot and her grandmother Mavis and her mother Evelyn actually feel, and what they’ve actually gone through. But if you can accompany the family through all of these hard decisions, just like Dot is doing, I think that’s where people can start to show solidarity. Because solidarity isn’t about empathizing, it’s about bearing witness and being there. And that’s what we’re asking the player to do.